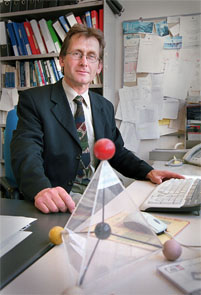

Professor of Chemistry Ben Feringa supervises his 100 th PhD student

This week, on 13 December, organic chemist Prof. Ben Feringa will look on as his 100th student is awarded a PhD. The University is proud to see one of its leading professors reach this prestigious milestone.

Feringa is one of the most creative and productive chemists of our time. In 1999, he was the first person in the world to develop a molecular engine powered by light energy. And in 2011, he linked four of these engines to a chassis, creating a molecular vehicle. ‘Nanomotoring, test-driving a molecular four-wheeler’ was the headline in an edition of Nature featuring an article that described how the vehicle moved in a controlled fashion. Feringa is a Spinoza Prizewinner, Academy professor, vice president of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences (KNAW) and winner of countless global awards. He is one of the few people who can rightly call himself a top researcher.

Playground

Apart from being a top researcher, Feringa is also a passionate teacher. ‘The only reason for all that pioneering research in the lab is to introduce students and PhD candidates to the research frontline,’ he says. ‘I see a PhD project as a playground for acquiring knowledge and experience, where students work independently on a complex problem with stiff international competition within a limited period of time – that will stand them in good stead throughout their career. I always tell my PhD students to make optimum use of those four years. Thirty years from now, it will be their job to ensure that our economy can compete with the rest of the world.’

Second to none

Standards are high in Feringa’s laboratory. ‘I can be difficult to please. It’s not about the quantity of theses we produce, it’s about the quality. My mentor Hans Wijnberg referred to this as 'second to none'. I see my PhD students as the Messis of science and give them the space they need to give their all. After four years, I expect them to be better than me in their chosen field. And the work they produce must be recognized in other countries. That’s where the competition is; we have to stay ahead.’

Making discoveries

Feringa selects candidates for a PhD position on the basis of creativity at the lab bench. ‘I’m not that interested in exam results. I want to know if they think about things and are keen to make discoveries, and if they’ve got the guts to try a new approach.’ He thinks that every PhD research project should throw up something new. ‘One of the first things I check when students arrive for a Bachelor’s or Master’s degree programme is whether they can work on their own. We encourage this by sending them to labs in other countries or on an industrial internship alongside the regular programme. This helps them to become self-sufficient and gives them the basis they need to design their own project here.’

The answer to everything

In his inaugural lecture in 1989, Feringa referred to the computer in The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. It had just one command: ‘to find the answer to life, universe, everything’. Although that is science fiction, Feringa acknowledges that his research has certainly expanded over the years. At national level, he is pooling his resources within an ambitious Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO) gravity programme, while the scope of his own ongoing research has broadened and deepened significantly. ‘The molecular systems we work with have become increasingly complex, as have the questions we ask. This is why we try to form working relationships with international partners and physicists and biologists from our own faculty.’

In addition, these days Feringa sits on numerous committees. Travel, attending meetings and giving lectures has become an important part of his work. ‘It’s quite a relief to come into the lab after a long meeting in The Hague, but I’m very much aware that if we want to uphold the quality of science, we need to make ourselves heard. You have to give something back. When it comes right down to it, the future and our students are all that count. Our society will sorely need the talent we are nurturing here to preserve our prosperity and overcome the scarcities of the future.’

More news

-

16 October 2025

Creating sustainable batteries to power the energy transition

-

15 October 2025

Night of the Night 2025

-

08 October 2025

Not all plastic needs to be bio-based or biodegradable