Ancient Siberian Hunters Survived the Ice Age by Inventing Pottery and Eating Fish

Scientists discovered some years ago that the world’s oldest pottery was invented during the last Ice Age. However, what foods were cooked in these ancient pots has long remained a mystery. This new research answers these questions, and provides some unexpected insights into human responses to past climate change .

The last Ice Age reached its deepest point between 26,000 to 20,000 years ago, forcing humans to abandon northern regions, including large parts of Siberia. From around 19,000 years ago, temperatures slowly started to warm again, encouraging people to move back into these vast empty landscapes. This was a precarious time for humans, who were still living in small mobile bands, as most large animal species like mammoth were in terminal decline, plus climatic conditions continued to flip unpredictably between warmer and cooler conditions.

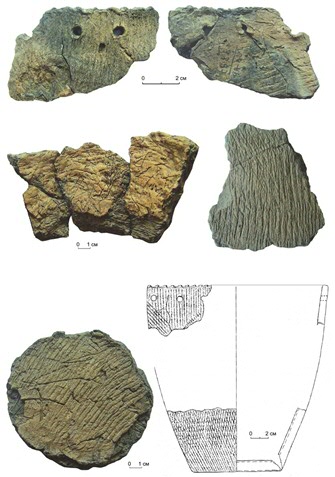

From around 16,000 years ago, we start to see some of these groups inventing radically new kinds of survival technology - this includes some of the world’s oldest examples of clay cooking pots. This ancient pottery starts to appear in small quantities at a number of sites on the Amur River in the Russian Far East between circa 16,000 and 12,000 years ago.

Why these pots were first invented in the final stages of the last Ice Age has long been a mystery, as well as the kinds of food that were being prepared in them. Staff of the Arctic Centre at the University of Groningen joined colleagues from Japan, Russia and the UK to solve these questions, and their findings are published on February 1st 2020 in the leading journal Quaternary Science Reviews.

The study extracted and analyzed ancient fats and lipids that had been preserved in pieces of ancient pottery, whose dates ranged between 16,000 and 12,000 years ago:

- The study proved that pottery from sites of the Osipovka Culture along the lower parts of the Amur River were being used to process fish, most likely migratory salmon, which offered local hunters an alternative food source during periods of major climatic fluctuation.

- An identical scenario has also been identified by the same research group in the neighboring islands of Japan, where pottery first appears around 16,000 years ago, during a period of much colder temperatures. Again, this ancient pottery in Japan was used to process salmon, perhaps when the hunting economy was plunged into a “climatic crisis”.

- However, the new study also identified that pottery from sites of the Gromatukha Culture higher up the Amur River were being used in completely different ways: to cook land animals, probably to extract nutritious bone grease and marrow during the hungriest seasons.

- Finally, the new study also demonstrated that the world’s oldest clay cooking pots were being made in very different ways in different parts of Northeast Asia: this appears to indicate a “parallel” process of innovation, where separate groups that have no contact with each other started to move towards similar kinds of technological solution under times of climate stress.

- Pottery quickly proved to be highly attractive tool for the processing of aquatic and terrestrial resources and ancient hunter-gatherers adopted it extremely widely, especially after the onset of the warm Holocene period around 11,000 years ago. This was long before any transition to farming.

Shinya Shoda

of the National Research Institute for Cultural Properties in Japan, lead Author of the study, says: We are very pleased with these latest results because they close a major gap in our understanding of why the world’s oldest pottery was invented in different parts of Northeast Asia in the Late Glacial Period, and also the contrasting ways in which it was being used by these ancient hunter-gatherers. There are some striking parallels with the way in which very early pottery was used in Japan, but also some important differences that we had not expected – this leaves many new questions that we will follow up with future research”

Peter Jordan , Director of the Arctic Centre at the University of Groningen in the Netherlands, and senior Author of the study, says: “The insights are particularly interesting because they suggest that there was no single “origin point” for the world’s oldest pottery – we are starting to understand that very different pottery traditions were emerging around the same time but in different places, and that the pots were being used to process very different kinds of resources. This appears to be a process of “parallel innovation” during a period of major climatic uncertainty, with separate communities facing common threats and reaching similar technological solutions.”

Oksana Yanshina , Senior Researcher at the Kunstkamera in St. Petersburg, was leader of the Russian Team, and a co-author, and says: “This study resolves some major debates in Russian Archaeology about what drove the emergence and very earliest use of ancient pottery in the Far Eastern Regions. But at the same time, this paper is just a small but important first step. We still need to do many more studies of this kind to fully understand how prehistoric societies innovated and adapted to past climate change. And perhaps this will also provide us with some important lessons about how we can better prepare for future climate change.”

Oliver Craig , Director of the BioArch Lab at the University of York where the analyses were conducted, says: This study again illustrates the exciting potential of new methods in archaeological science: we can extract and interpret the remains of meals that were cooked in pots over 16,000 years ago.”

Information

Read the article.

Senior Author: Professor Peter Jordan, Arctic Centre (Director) / Groningen Institute of Archaeology, University of Groningen, the Netherlands.

| Last modified: | 21 April 2020 3.15 p.m. |

More news

-

06 May 2024

Impact: Utilization of geospatial data within international development cooperation

One of students nominated for the Ben Feringa Impact Award 2024 is Jonas Göbel. Göbel is nominated because of his internship research around the utilization of geospatial data in the field of international development cooperation.

-

03 May 2024

NWO Impact Explorer for Suzanne Manizza-Roszak's impactful postcolonial literary research

Suzanne Manizza-Roszak, Assistent Professor English at the Faculty of Arts has received an Impact Explorer grant from the Dutch Research Council (NWO) for her postcolonial literary research and the project to translate the results into social...

-

29 April 2024

Learning to communicate in the operating theatre

The aios operates, the surgeon has the role of supervisor. Three cameras record what happens, aiming to unravel the mechanisms of 'workplace learning'.