Tumor gone, but where are the words?

Once the tumor has been removed from their brain, children can usually speak normally. So why does about a third still lose their ability to speak in the days afterward? Vânia de Aguiar wants to be able to predict that—and many parents, children, pediatric oncologists, surgeons, nurses, and speech therapists are joining her. At the Faculty of Arts, she researches speech and language problems in children who have had a tumor in the cerebellum.

Text: Helma Erkelens / Photos: Reyer Boxem

'When they come out of surgery, if everything went well, everyone is optimistic: the tumor is gone, and the child can speak. So, it’s a huge shock for parents when that suddenly stops. Luckily, we now know that this can happen and that it’s temporary, but it remains stressful,' says Vânia de Aguiar. She explains that mutism (loss of speech, ed.) usually occurs within 72 hours after surgery and can last from a few days to weeks. 'Fortunately, most children do not develop it, but some stop speaking completely after cerebellum surgery, while others can only manage a few words or very short sentences with great difficulty.'

De Aguiar and her team study a specific part of the brain initially known only for its role in movement: the cerebellum. Research on people with brain injuries has shown that it is also essential for language and speech. The cerebellum is located in the brain region called the posterior fossa, from which the name of the condition is derived: posterior fossa syndrome.

The problems were already there

Because the loss of speech is temporary, it was long assumed that the cause lay in the surgery itself. 'To save a child’s life, the surgeon has to cut into the brain regions where the tumor is located. They can’t always avoid damaging healthy parts. But a tumor itself also damages the brain. It can infiltrate, push aside, or compress areas—faster or slower. So damage may have occurred even before surgery, but only become noticeable after the procedure,' explains de Aguiar. There is some evidence for this: 'Some recent smaller studies show that speech and language problems were already present in the period before the surgery.'

You see that many children with a cerebellar tumor have speech and language impairments. These are related to speech motor skills: breathing, sound production, and articulation.

Groningen control group

Her team is searching for the cause and wants to know whether the brain tumor and surgery affect children’s later speech and language development. They do this in collaboration with other research centers participating in the European Cerebellum Mutism Syndrome Study—an initiative of Rigshospitalet in Copenhagen. For this study, seventeen hospitals in eleven countries collect speech and language data from children with brain tumors in the same way, starting already before surgery.

From the Faculty of Arts in Groningen, De Aguiar is building a database with the same data from healthy children—the control group. 'Four- to sixteen-year-olds, mostly from Groningen and the surrounding area, to keep it practical, but we are also working on data collection of controls in Italy and the UK.'

The boy and the fish

Part of the assessment that all hospitals conduct involves children telling the story of the boy and the fish. 'They do this using pictures from a picture book. The test is administered before and after surgery, and repeated two months and a year later. The nice thing is that you can ask a four-year-old but also a sixteen-year-old. Of course, children are always compared within their age group.' Children in the control group also do this test, but only once.

Different languages

All children tell the fish story in their native language. How can you then compare speech and language levels? 'We study basic building blocks of language that occur in every language. These can have different features, such as in vocabulary and in grammar. For speech, we look at how well sounds are articulated and whether voice quality is appropriate. So we don’t compare children across languages, but compare all patients with healthy children. That’s why we need control groups that speak the same languages as the patients,' explains de Aguiar. She also makes comparisons between patient groups.

Nasal speech

"In every country, we see that many children with a cerebellum tumor have some degree of speech and language limitations. We see no differences in language between children who do or do not develop mutism after surgery—but there are differences in speech. That concerns speech motor skills: breathing, producing sounds, the ability to articulate." One of her PhD students studies this and found that children who develop mutism sound more hypernasal compared to those who do not, already before surgery.

Long-term effects

Sometimes she receives an email from an unfamiliar high school teacher. 'It might say, "I have a student taking final exams this year. She’s doing well in all subjects, but is going to fail English. How can that be? She had brain tumor surgery once."' Pediatric oncologists also occasionally send her such messages. 'I want to know whether learning a second language, can cause problems in former patients, and why. We may be talking about a tumor from years ago!' Research on the long-term consequences of brain tumors is high on her priority list.

Brain damage evolves

These worried emails show that brain damage is not static. 'Children continue to develop, and apparently the brain develops differently when it’s damaged. The cerebellum is important for learning. If your learning mechanism is impaired by the tumor or surgery, you will learn more slowly afterward. So the developmental gap between healthy children and those who have had brain surgery widens over time. It may go unnoticed for a long time because these children reach milestones like reading and writing, apparently like everyone else. Only when the bar is set very high, like in a final exam, they fail. That’s sad for the children and harmful to their future prospects. We know from adults who had a brain tumor as a child that they, on average, achieve a lower level of education, work in less qualified jobs, and have a lower socio-economic status. That’s why it’s necessary to understand the root causes.'

Preventive speech therapy

She advocates that all children have their speech and language assessed by a speech therapist or clinical linguist after cerebellum tumor removal to determine if help is needed. 'Children with brain tumors are not routinely, and not often enough, referred to speech therapy.'

It is an unexplored field, ripe for research. One of De Aguiar’s researchers is now surveying hospitals worldwide about diagnostic and treatment practices for children before and after brain tumor surgery. 'I hope we can establish an international standard.'

A high school senior excelled in every subject except English. She had previously undergone surgery for a brain tumor.

Preventive speech therapy

She advocates that all children have their speech and language assessed by a speech therapist or clinical linguist after cerebellum tumor removal to determine if help is needed. 'Children with brain tumors are not routinely, and not often enough, referred to speech therapy.'

It is an unexplored field, ripe for research. One of De Aguiar’s researchers is now surveying hospitals worldwide about diagnostic and treatment practices for children before and after brain tumor surgery. 'I hope we can establish an international standard.'

Vânia de Aguiar

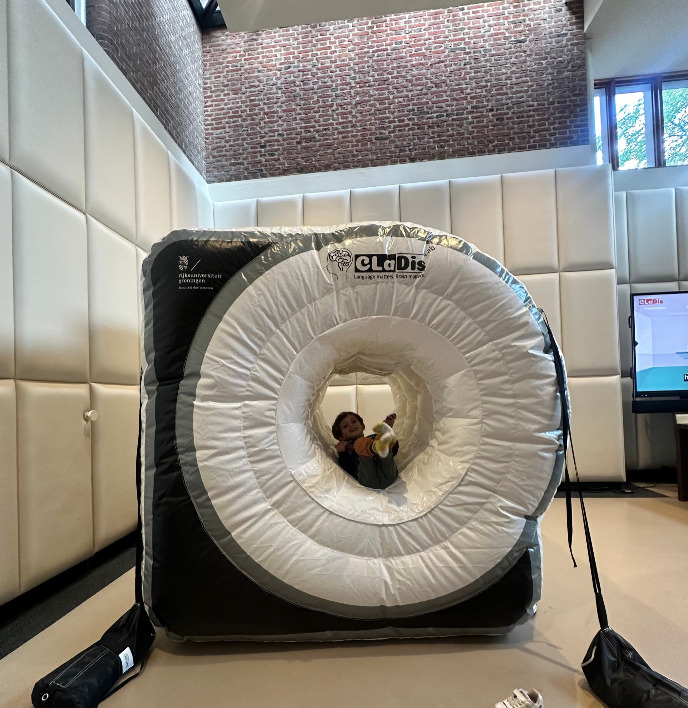

As an expert in clinical linguistics and neuroscience, Associate Professor Dr. Vânia de Aguiar is interested in language and the brain. Research on mutism in children after cerebellum tumor surgery is one of her focus areas. At the CLaDis Lab of Neurolinguistics, she also studies other language disorders in children, such as developmental language disorder (DLD). Part of the DLD research involves an MRI scan, for which children must lie still in a narrow tube for 30 minutes to make a 3D photo of their brain. Recently, they prepare children for this using an inflatable MRI.

She also collaborates extensively with the Pediatrics Department of the University Medical Center Groningen, for example studying how brain changes are related to changes in language. She compares the brains of children treated for a brain tumor with those of healthy children.

Do you want to contribute?

Many children support other children with cancer in various ways, from charity runs and collecting bottles to sleeping in a tent in the garden for a year.

But you can also participate in Vânia’s research! To gather scientific evidence on how the brains of children who had brain surgery develop, she needs many healthy children in the control group.

Vânia hopes that the knowledge gained will ensure patients receive the right speech and language therapy at the right time so their brains can develop as well as healthy children’s. If you want to contribute, you can sign up for Vânia’s research here.

More news

-

19 January 2026

Digitization can leave disadvantaged citizens in the lurch

-

13 January 2026

Doing good in complex situations