Mysterious matter mapped

In the almost empty space between stars lurks something that blocks starlight at certain wavelengths. Although it was first observed almost a hundred years ago, astronomers still have no idea what this ‘something’ is. A team of scientists, including University of Groningen astronomy professor Amina Helmi, has now published the first map of the spatial distribution of this mysterious matter.

The space between stars is almost completely empty. Even when astronomers say that ‘dense’ dust clouds are present, the amount of matter is still no more than a few atoms per cubic centimetre. But as the Universe is incredibly big, this still amounts to a lot.

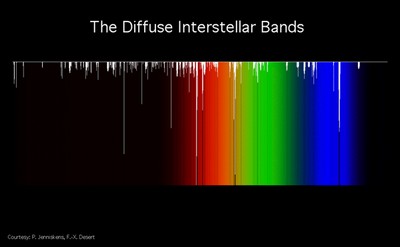

It is therefore of interest to establish what exactly is present between the stars. Astronomers who wish to study these interstellar clouds often search starlight for ‘ absorption lines ’, which are places where there is no light when you would expect there to be. Viewed from the Earth, when a star is behind the cloud the dust will absorb the starlight at specific wavelengths, which are indicative of the kind of matter that is present.

In the lab, you can find out which atoms or molecules absorb which wavelengths. If you see light absorbed at the same wavelength in starlight, you then know what type of matter is between the Earth and the star.

At least, that is the theory. In practice, it can be more complicated. Astronomers first observed one class of absorption lines, the ‘Diffuse Interstellar Bands’ (DIBs), in 1922, but are still unable to link them to any specific atom or molecule. To gather more information on these DIBs, an international team set out to produce a map of the spatial distribution of one such DIB, which absorbs light at a wavelength of 862 nanometres.

This was easier said than done. First, the team had to know the distance between the Earth and a huge number of stars. Then they had to measure any absorption at 862 nanometres, which would indicate the presence between the Earth and a particular star of the mysterious matter that causes this DIB. To complicate matters, the DIBs are a very weak phenomenon, which you can only observe in the light of stars that are very hot and therefore very bright.

To accomplish all this, the team used a catalogue of half a million stars, whose distance from Earth was measured in the RAVE survey . Amina Helmi, astronomer professor at the University of Groningen Kapteyn Institute, played a prominent role in this survey.

‘Together with my team, I published the first distance measurements of the survey in 2010’, she says. ‘ ‘And we have provided the DIB project with the algorithm to determine these distances .’ This was a vital step in the construction of the 3D map of the DIB, which has now been published in Science.

In the Science paper, the scientists describe the spatial distribution of the source of the 862-nanometre DIB in part of the Southern Hemisphere, fanning out from Earth for about 10,000 light years. This DIB is somewhat similar in distribution to known interstellar dust clouds in the region. ‘But the DIB source and the dust clouds are not identical’, Helmi remarks. In the vertical plane (perpendicular to the disc which contains most of the stars in the Milky Way) there is indeed a marked difference. ‘This means that DIBs are not simply associated to any type of dust grain.’

The cause of the DIBs is still a mystery. Why such an interest in solving this mystery? Helmi: ‘We know there is something there, but we don’t know what it is. However, there are some indications that the DIBs are caused by carbon compounds – organic molecules that are the building blocks of life. Which of course makes them even more interesting.’

Reference: Pseudo–three-dimensional maps of the diffuse interstellar band at 862 nm , J. Kos et al, Science, Vol. 345, Issue 6198, p 791-795, 15 August 2014.

| Last modified: | 26 January 2016 12.40 p.m. |

More news

-

13 May 2024

Trapping molecules

In his laboratory, physicist Steven Hoekstra is building an experimental set-up made of two parts: one that produces barium fluoride molecules, and a second part that traps the molecules and brings them to an almost complete standstill so they can...

-

29 April 2024

Tactile sensors

Every two weeks, UG Makers puts the spotlight on a researcher who has created something tangible, ranging from homemade measuring equipment for academic research to small or larger products that can change our daily lives. That is how UG...

-

16 April 2024

UG signs Barcelona Declaration on Open Research Information

In a significant stride toward advancing responsible research assessment and open science, the University of Groningen has officially signed the Barcelona Declaration on Open Research Information.