‘The idea to become number one again made Britain a shattered nation’

Interview: Jelle Posthuma

A third of English children grow up in poverty. The infant mortality rate is among the highest in Europe, and most strikingly, British children are getting shorter. Yet the country was among the most egalitarian in Europe in the 1970s. Danny Dorling, a renowned English social geographer, shed light on these alarming developments in his latest book, 'Shattered Nation: Inequality and the Geography of A Failing State.' Recently, the Rudolf Agricola School for Sustainable Development in Groningen invited Dorling to discuss his work and insights into how Britain arrived at its current state.

|

In Shattered Nation, Dorling paints a grim picture of England. Telling, he says, is the week in which he submitted his manuscript to the publisher. That week, Liz Truss resigned as prime minister of England after only 49 days. The English tabloid The Daily Star had a webcam aimed at a lettuce. Mockingly, the newspaper wondered: who would last longer, Liz Truss or the lettuce? The latter turned out to have a longer shelf life.

Dorling: 'The example of the lettuce and Liz Truss illustrates that my book was actually no longer needed. Everyone in Britain knew we were a 'shattered nation'. I made some changes to the book before publication to make it useful anyway. So far, nobody has said that Shattered Nation is wrong. In a way, that's very sad.'

How different are Dorling's own childhood years. In his book, the social geographer describes Oxford of the early 1970s, the place where he grew up. 'For most people, things were getting better. Many of them worked in the what is now BMW factory, and were able to get a mortgage and start a family at twenty-five. That's not just how I remember it; the figures also show this.'

According to Dorling, England was a strongly egalitarian society in those years, with the important note that things were different for women and minorities. 'There was income equality, children went to the same schools and we had very good social housing. Other countries came here to see how we did it. In essence, Britain was a Scandinavian country. Only in Sweden there was more equality in the 1970s.'

What does Oxford look like now, fifty years later?

In Oxford, the factory jobs have disappeared. The cars are now assembled by 1,200 robots. The poor have been pushed out of the city. The house where a factory worker used to live with his family has become unaffordable. Maybe a young professor at Oxford, with help of their parents, can only just afford it. They are very happy to get a house, even though it is actually a shit house, since it is 50 years older and usually more dilapidated.

Over the past fifty years, the rich became richer. Meanwhile, the 'cost of living crisis' is affecting millions of Brits. Banks only want to lend money to our country at high interest rates, which says a lot about the trust in our financial system. A third of children grow up in poverty. Neonatal mortality is among the highest in Europe, and most strikingly, children in Britain are getting shorter. In several lists, we rank among Eastern European countries. I'm not saying the Eastern European countries belong there and we don't, but it says a lot about England's decline.

What happened?

For that, we have to go back in history. After World War II, the Labour Party (the social democratic party, ed.) won the elections, against the odds. Under the leadership of this progressive government, significant socio-economic reforms were introduced, for instance in housing, health and education, resulting in greater equality.

At the same time, the well-off became very upset. After the war, they lost their big houses. They also had to start working in the banks in the London City. It sounds crazy, but they hated it, given that their grandfathers ruled India. England no longer was an 'empire' with colonies. From the 1960s, this group of well-off people began to stir 'on the right'. They aspired to make England the world's number one again. According to them, the British people were still the 'cleverest people' on earth. Post-war equality was 'cutting down the tall poppies' – anyone who excelled was constrained. At least, that was what members from this group claimed.

This idea - to make Britain number one again - is important to understand English politics. You can see it when Britain joined the European Economic Community (EEC), in 1973. All the memos from that time show that England joined to gain market access. We entered to become better than the rest, not to become European citizens.

When did this group of well-off people gain political influence?

From the 1970s, the political climate tilts to the right. Remarkably, it starts within the Labour Party. In 1976, Labour leader James Callaghan gave a speech in which he more or less argued that things had gone a bit too far with equality. A few years later, Conservative leader Margaret Thatcher came to power. Despite mass unemployment, she managed to maintain her popularity, thanks to lower taxes and a small, won Falklands war. In 1990, she was succeeded by John Major, also a Conservative politician.

Although Labour leader Tony Blair became prime minister in 1997, the political climate remained right-wing as Labour had moved to the right. When Thatcher was asked about her greatest success, she replied: ''Tony Blair and New Labour. We forced our opponents to change their minds.'' Another example: in 2014, the British Conservative Party in the European Parliament left the right-wing coalition to join the more pro-fascist parties. In short, the whole political arena shifted to the right.

Has this led to Brexit?

Far-right politics and ‘making England number one again-thinking’ provided fertile ground for the Brexit. In 2015, pressured by other members of the Conservative Party, Prime Minister David Cameron held a referendum on leaving the EU. With the referendum, he hoped to regain control over the party, yet he never expected the Leave camp to win. The referendum outcome was a shock to the establishment. I believe it fits a 'shattered nation': even those in power are no longer in control.

Still, the Brexit was not all bad, at least not for Europe. If 'remain' had been chosen, Brexit sentiment would not have gone away. Britain was always an infection within the EU. With our obstinate stance, we helped creating the backroom politics and secret deals in Brussels, exactly what we hated about Europe. Moreover, the Brexit shows that the European Union is indeed a democracy: if you choose to leave the Union, you are free to do so. An added benefit is that other member states will now think twice before they want to leave the EU.

How do you feel about the recent political developments in the Netherlands?

I think it is similar to the victories of the more pro-fascist parties in Italy and Greece. At the same time, we should not forget the recent elections in Poland. In the news, a lot of attention is paid to the rise of the radical right, but the opposite happened in Poland. You have to celebrate the victories as well. The rise of the radical-right also makes the 'left' less lazy. You see it in the younger generation, who choose to go to a political meeting instead of going for a drink.

England, my country, is now viewed with pity by the world, which is something the Netherlands wants to avoid. But things can definitely change in England too. Look at Scotland. There, an important law was recently passed to tackle child poverty. In the younger generations, I see the will to change something, also in England.

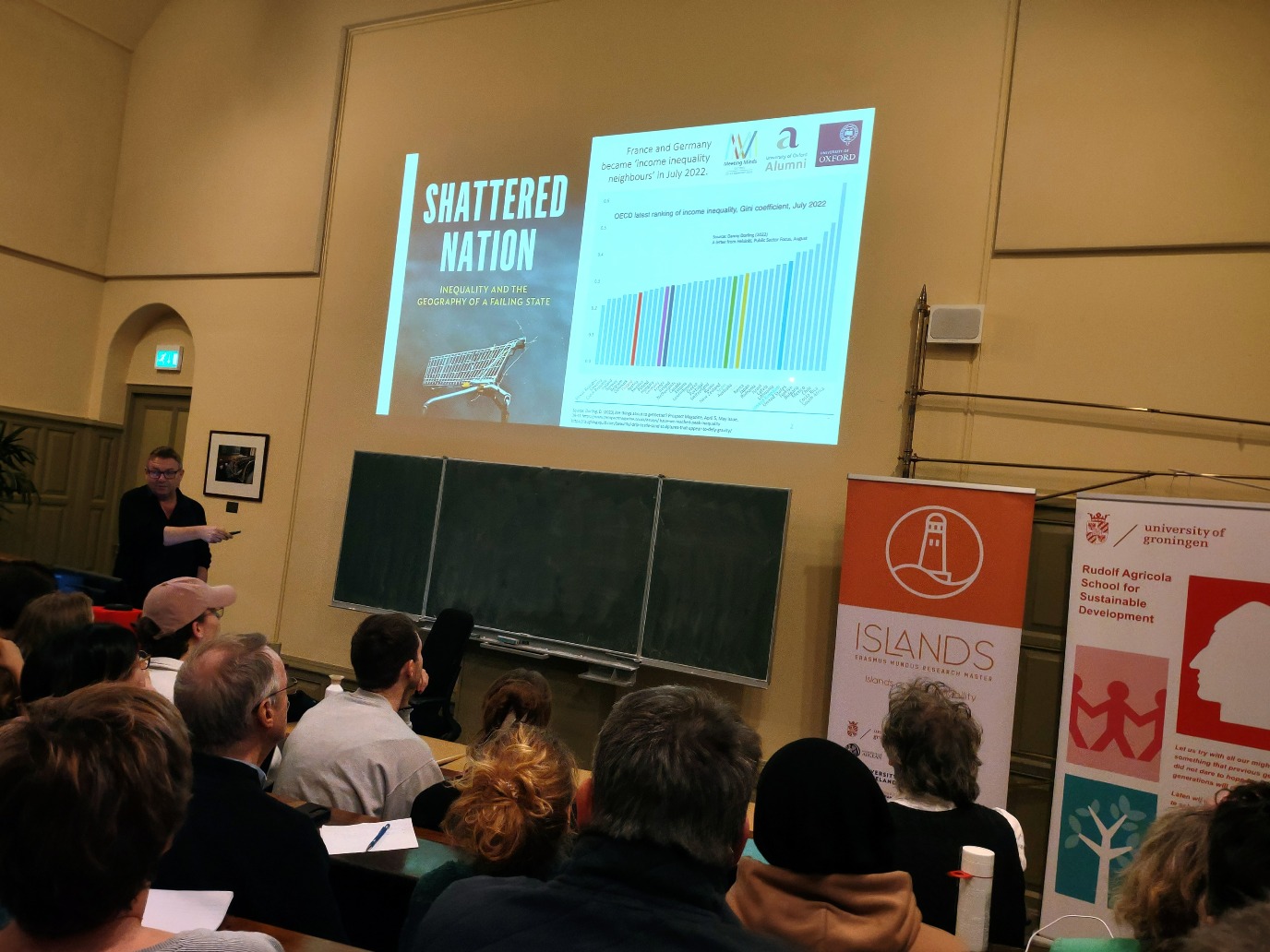

On 19 December, Dorling gave a well-attended guest lecture in Groningen. He was invited by Dimitri Ballas, professor of Economic Geography, and 'fellow' at the Rudolf Agricola School for Sustainable Development. You can read a report of the lecture here.

| Last modified: | 18 January 2024 2.52 p.m. |

More news

-

13 May 2024

Trapping molecules

In his laboratory, physicist Steven Hoekstra is building an experimental set-up made of two parts: one that produces barium fluoride molecules, and a second part that traps the molecules and brings them to an almost complete standstill so they can...

-

29 April 2024

Tactile sensors

Every two weeks, UG Makers puts the spotlight on a researcher who has created something tangible, ranging from homemade measuring equipment for academic research to small or larger products that can change our daily lives. That is how UG...

-

16 April 2024

UG signs Barcelona Declaration on Open Research Information

In a significant stride toward advancing responsible research assessment and open science, the University of Groningen has officially signed the Barcelona Declaration on Open Research Information.