Archaeologists offer long-term perspectives. What archaeology can tell us about wetlands and the future of the Netherlands | Interview with Dr De Haas and Dr Schepers

Interview: Marco in 't Veldt

Dr Tymon De Haas is an archaeologist of the Mediterranean. Dr Mans Schepers works on the prehistory of Northwest Europe. On the face of it they are two quite different specialisations, yet they work together frequently. Their shared interest: the development of ‘wetlands’. They are comparing the Pontine marshes in Italy with the Onlanden near Groningen. Recently they edited an issue of the Journal of Wetland Archaeology together.

Schepers: 'Wetlands’ is often translated as ‘marshes’ but it actually includes any piece of land that has to deal with lots of water, including high moors, low moors and flood plains.'

De Haas: 'The current rapid climate change and the collapse of biodiversity have drawn attention to the importance of wetlands around the globe. Wetlands can store CO2 and water and offer enormous biodiversity. Unfortunately, the thinking about these areas tends to be fairly static, without attention to their long human history.'

De Haas: 'That is why we're both active in the Agricola Future Fit Villages research group. It considers the future of villages and the rural areas. As archaeologists we can contribute a long-term perspective.'

What makes wetlands interesting to archaeologists?

Schepers: 'A large part of the Netherlands is - reclaimed - wetland. Ultimately, we live in a river delta. The soil is generally fertile, and wetlands provide all manner of natural resources. As a result they were inhabited fairly early on, and they have a long history of habitation.'

Why are you studying the Pontine marshes?

De Haas: 'The University of Groningen has been studying the Pontine marshes in Italy since the 1980s, particularly because they have such a long history. The marshes – close to the important city of Rome – have known periods of reclamation by the Romans and by various popes. In the 1930s they were ‘definitively’ reclaimed under the Fascist regime.

When we carry out research, we find traces of everything people have done there over thousands of years. The landscape changed all the time. We are looking at physical developments, but also at the social context and at perceptions of landscape. For a long time, reclamations were seen as positive, as they brought ‘civilisation.’ These days we attach more value to biodiversity and that leads to different management choices. You can see that in Onlanden, where agricultural ground has been transformed into water storage and nature.'

How do you study these areas?

De Haas: 'Digs are good for studying individual settlements, but they don't work if you - like us - are interested in landscapes. The Pontine marshes cover an area of one hundred and twenty square kilometres. You can't begin to dig that. We start by walking around the area. What type of remnants can you see? Do you see traces of former farms? Any shards? We also study old aerial photographs and maps, which help to identify traces of different phases of inhabitation. These days we also have so-called ‘remote sensing’ technologies that are used to detect disruptions in the Earth’s magnetic field. That makes it easy to trace previous canals and ditches. If you can do that over large surface areas, you can expose complete parcelisation patterns. (Laughs) We're lazy archaeologists, we don't dig too much.

We also drill the soil in former ditches and canals. We take soil samples. With the C14 method we can see how old they are. We analyse plant remnants and pollen to identify the plants that grew there.”

Schepers: 'That enables you to reconstruct environmental conditions, changes in land use, practices that were used to manage resources, and the impact of human activities on the wetland ecosystems.'

Mussolini reclaimed the Pontine marshes. But didn't the Romans do that before him?

'Correct, the area was reclaimed for food production, but as a result of all sorts of technical challenges, social changes, and natural processes, these reclamations did not last. For example, peaty ground subsides if you reclaim it, and the land ends up lower. That worsens your problems with water drainage. That could only be solved with industrial pumps. These days it is an area of intensive agriculture, where grain, vegetables and fruit are grown.'

What is the importance of your cooperation and of comparing these areas?

De Haas: “The choice of areas is actually fairly pragmatic. We were already doing research when we met, and we found out that we were working on the same themes but from a different research angle. We learn a lot from each other. The best bit is that you can provide context to the discussions and plans of today. In Italy people like to talk as if Mussolini was the one to finally drain the marshes, but we question that from a historical perspective. They already have massive problems with shrinkage and drying out. Farmers tell us that it is already no longer profitable to cultivate something. Perhaps there, like in Onlanden, partial or full rewilding could be an option for the future.”

What does your research have to do with ‘sustainability’?

De Haas: “Policy-makers often have an extremely short-term perspective. To them, 2050 is way in the future. To us it is the day after tomorrow. You need to think at least in terms of 2200.

On the other hand, there is often a desire to return certain landscapes to some sort of ‘original state’. ‘That used to be forest’, is what they say. But that isn't true at all. Our research demonstrates that the landscape changes all the time. You can only make meaningful statements if you look to the long-term past of a landscape.'

Schepers: 'Terms like salinisation, drying out and climate change imply a process, a time component. For example, if you consider the shrinkage of peat lands, we can use our knowledge to link the past to the future. If it went like that back then, and it is like this now, what will it be like in a hundred years’ time?

There are expectations that parts of the Netherlands will be ten to fifteen metres below sea level by that time. Even if you could manage the height of dikes that would require, you couldn't manage the pumping!'

So what is the solution?

Schepers: 'You can capture lots of CO2 with wetlands and halt climate change. It also produces an enormous biodiversity. In our profession, we look at these developments with a sense of regret. When the Onlanden were turned into wetlands, many traces of the medieval landscape disappeared forever, traces we would have liked to have studied, farms we would have liked to have dug up.

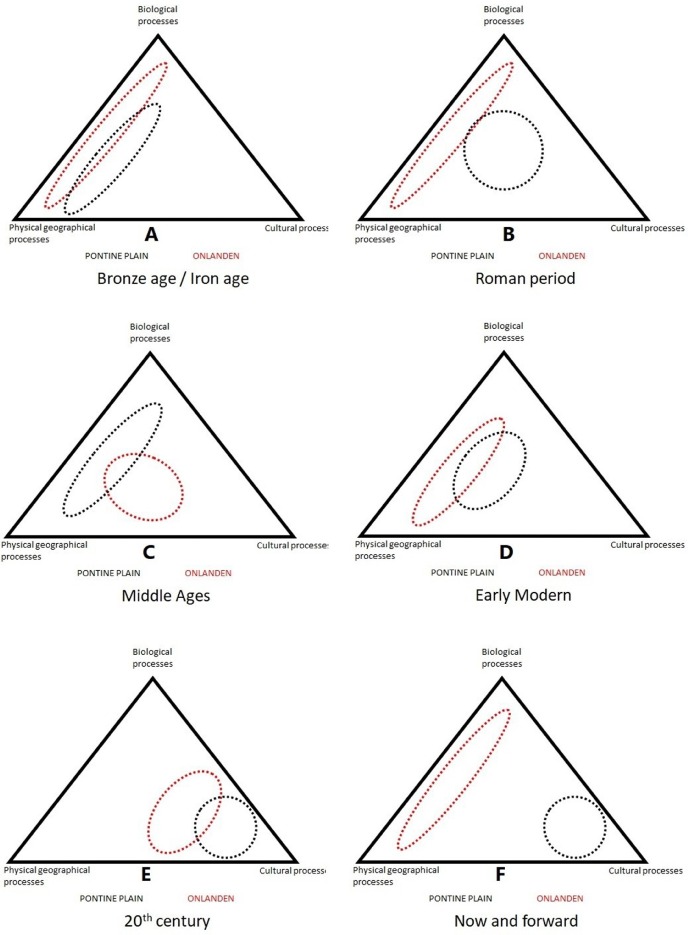

The triangular model. Top: biological processes, left physical geographical and right cultural processes.'

What does the comparison produce? What is an important conclusion as far as you're concerned?

De Haas: 'Recently, we published an article where we compared the Pontine marshes and Onlanden in a triangular model. Generally people talk about landscapes in terms of a duality: nature - culture.

We add a third component: physical geography. People consider that unchangeable but our research demonstrates that processes, such as peat oxidation, soil compaction, and sedimentation caused by floods are extremely important factors!

The triangular model considers such processes to be just as important as the archaeologically tangible cultural and environmental processes.'

Urgency

'We sense an enormous urgency in our work. On the one hand we hope to use our knowledge to contribute to thinking about sustainable use of the landscape. On the other, developments - such as Onlanden – can wipe out soil archives and that makes this type of research urgent.'

| Last modified: | 22 March 2024 3.40 p.m. |

More news

-

29 April 2024

Tactile sensors

Every two weeks, UG Makers puts the spotlight on a researcher who has created something tangible, ranging from homemade measuring equipment for academic research to small or larger products that can change our daily lives. That is how UG...

-

16 April 2024

UG signs Barcelona Declaration on Open Research Information

In a significant stride toward advancing responsible research assessment and open science, the University of Groningen has officially signed the Barcelona Declaration on Open Research Information.

-

02 April 2024

Flying on wood dust

Every two weeks, UG Makers puts the spotlight on a researcher who has created something tangible, ranging from homemade measuring equipment for academic research to small or larger products that can change our daily lives. That is how UG...