Predators dictate bird incubation habits

Birds facing many predators at their nests have longer incubation spells than birds that do not have this problem. The latter can more easily change shifts without risking foxes or crows discovering their nests. This is what Czech and Belgian biologists Bulla and Kempenaers and researchers from Groningen have discovered. They have shown that there is great variety in shorebird incubation patterns. Whereas the birds of one species will be relieved by their mates every few hours, those of another can easily spend 20 hours on the nest. Fieldwork spanning 20 years that studied 32 species has revealed that predator avoidance dictates bird incubation habits. The findings were published in the journal Nature on 24 November.

Imagine a bird, a red knot say, that has just relieved its mate and is now sitting on their precious clutch on a nest on the cold tundra. This will be a long sit because its mate will be away for up to 20 hours. At the same time, a few thousand kilometres southwards a black-tailed godwit sitting on its nest in a meadow sees its mate appear after six hours, raring to take over. The ringed plovers that nest on gravel beaches are even more extreme, relieving each other every two to three hours.

Variation

It was thought that this striking variation in incubation spells was due to significant differences in shorebird habitat and that these patterns were primarily determined by the energy requirements of the birds and the availability of food, and regulated by the circadian clock. A group of 76 bird researchers, four of whom came from the University of Groningen, disproved these assumptions.

First author Martin Bulla analysed data from 729 nests belonging to 32 different species of shorebird that was collected over a period of 20 years by a large team of shorebird researchers all around the world. The team included five researchers from the Flyway Ecology group of University of Groningen professor Theunis Piersma. Bulla found that the extreme variation in nest attendance patterns was determined by neither environmental factors nor daylight variation but rather the strategies adopted by the birds to prevent hungry predators from snatching their eggs.

Those species whose main strategy was to remain hidden and who did not actively react to predators had longer incubation spells than those who actively tried to distract or drive away predators. We therefore should not pity the bird that must spend 20 hours on its nest, because this is the strategy that it and its mate have chosen to adopt. A bird that remains away for long spells of time is not leaving its mate to starve but is protecting the nest from lurking predators.

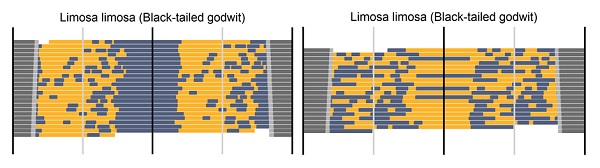

The next step is to find out whether birds can modify their incubation habits according to the annual population density of predators. ‘Actograms’ showing the activity of two pairs of black-tailed godwits nesting in Friesland give a first hint. The first pair exhibited normal behaviour: the male sat on the nest at night and the pair regularly relieved each other during the day. The second pair, which probably saw more predators by the nest, avoided regular swaps, and the less orange and thus more camouflaged female therefore spent more time on the nest during in the day.

The actograms show when the female (yellow) and male (blue) sat on the nest during a 24-hour period. Each row represents two consecutive days. The slanting light-grey bars represent twilight and correspond to when the sun is between an angle of 6° and 0° below the horizon. The dark-grey bars represent night and correspond to when the sun is > 6° below the horizon. The vertical black and grey lines represent midnight (24:00) and midday (12:00). Twilight and night have been omitted from the centre of the actogram to make the pattern visible.

Reference: M. Bulla et al., Unexpected diversity in socially synchronized rhythms of shorebirds. Nature, 24 november 2016, doi 10.1038/nature20563

See also the News & Views article Biological rhythms: Wild times in the same issue of Nature.

| Last modified: | 06 December 2016 3.30 p.m. |

More news

-

16 April 2024

UG signs Barcelona Declaration on Open Research Information

In a significant stride toward advancing responsible research assessment and open science, the University of Groningen has officially signed the Barcelona Declaration on Open Research Information.

-

02 April 2024

Flying on wood dust

Every two weeks, UG Makers puts the spotlight on a researcher who has created something tangible, ranging from homemade measuring equipment for academic research to small or larger products that can change our daily lives. That is how UG...

-

18 March 2024

VentureLab North helps researchers to develop succesful startups

It has happened to many researchers. While working, you suddenly ask yourself: would this not be incredibly useful for people outside of my own research discipline? There are many ways to share the results of your research. For example, think of a...