Failed experiment ends up in Nature

Three trips to Greenland resulted only in disappointment for climate researcher Harro Meijer from the University of Groningen Centre for Isotope Research. A few years later, however, the data from this failed field experiment on the ice cap suddenly proved extremely useful, and Meijer ended up contributing to a study that was published in Nature Climate Change on 4 January.

In 2005, Harro Meijer deposited a thin layer of artificial snow on the ice cap in Greenland. He returned in the subsequent two years to observe the layer as it gradually disappeared beneath a layer of snow. The reason for this research is explained here . When Meijer returned in 2006 and 2007, he found that the thaw had reached the ice cap, causing his experiment quite literally to melt away. This made it impossible to interpret the results.

‘In hindsight it was stupid’, Meijer says now. ‘One aim of our research was to record climate change. We chose a test area where our colleagues from Utrecht University had been working for years and where it always froze, but the climate change that we were actually trying to record meant that it now thawed there in the summer too.’

The spot where he worked was at an altitude of 1800 metres, which was relatively low. Meijer therefore moved to a location where the ice cap was three kilometres thick and where it did freeze all year round. He was able to conduct the experiment there instead. The data that he had collected in his first attempt was consigned to the back of a drawer, apparently useless.

That is where it would have stayed, if the melt in Greenland had not steadily reached higher areas. In 2012, the temperature on the entire ice cap rose above zero for a few days. This was unprecedented, and scientists began to wonder about the effect of all the resultant melt water.

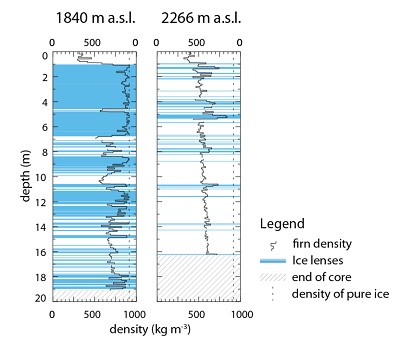

‘The upper 50 to 80 metres of the ice cap is made up of firn, old snow with an open structure. This can absorb melt water like a sponge’, Meijer explains. The question was whether this firn layer could also cope with huge amounts of water. An international team drilled into the ice cap to find out what exactly happened to the water.

‘They needed data for comparison’, says Meijer. ‘And one of the researchers, Dirk van As, knew that I had collected core samples from the upper three metres at an altitude of 1800 metres in 2006 and 2007.’ This was thus in the years immediately preceding the thaw in Greenland.

Water that seeps down into the ‘sponge’ of the firn refreezes there. The researchers discovered that large amounts of melt water form ‘ice lenses’, slabs of ice in the firn, sometimes kilometres in length, that block the flow of water. New melt water can no longer seep down, but instead flows down from the ice cap and over the ice. The amount of melt water flowing from the ice cap into the sea consequently increases. These are the findings presented in the Nature Climate Change article.

The large slabs of ice mainly form in the lower parts of the ice cap, such as the spot where Meijer conducted his failed experiment. ‘Our data served as a kind of historical check, and showed that in 2006 and 2007 some melt water had frozen in the firn, but this was in separate chunks. It is only in the last few years that the large slabs of ice have formed.’

This is how seemingly useless data found its way into a Nature publication. ‘It was pure coincidence that Van As knew me and knew about the experiment’, says Meijer. 'Databases have been established containing the results of fieldwork, including unpublished data as well. In the Netherlands, this goes by the name of the Netherlands Polar Data Centre .’ Perhaps ‘useless’ data will regularly prove useful in the future.

| Last modified: | 26 August 2019 12.15 p.m. |

More news

-

16 April 2024

UG signs Barcelona Declaration on Open Research Information

In a significant stride toward advancing responsible research assessment and open science, the University of Groningen has officially signed the Barcelona Declaration on Open Research Information.

-

02 April 2024

Flying on wood dust

Every two weeks, UG Makers puts the spotlight on a researcher who has created something tangible, ranging from homemade measuring equipment for academic research to small or larger products that can change our daily lives. That is how UG...

-

18 March 2024

VentureLab North helps researchers to develop succesful startups

It has happened to many researchers. While working, you suddenly ask yourself: would this not be incredibly useful for people outside of my own research discipline? There are many ways to share the results of your research. For example, think of a...